重新想象阅读障碍的支持:通过虚拟现实改变学习

CORPUS CHRISTI, Texas — The moment happened in a charter school classroom. As classmates looked on, one student pushed back his chair, raised his fist, and proudly declared he was heading to reading intervention — where he gets to play virtual reality (VR) games — because he’s dyslexic. In that instant, Dr. Aurelia O’Neil ’25 saw something remarkable: a student who grew from feeling ashamed of his learning differences to embracing them.

“With dyslexia, you’re constantly misunderstood,” O’Neil said.

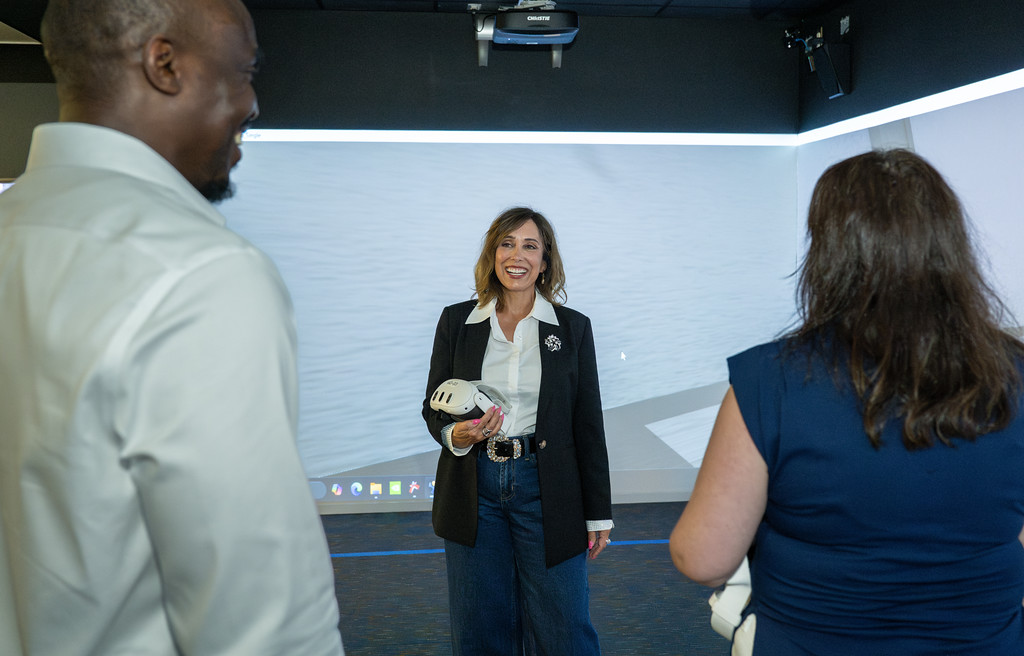

O’Neil, who recently graduated from Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi with a Ph.D. in Curriculum and Instruction, also works in the university’s Digital Learning and Academic Innovations (DLAI) office as an instructional designer. 在她的博士论文中,她探讨了阅读障碍专家如何将技术融入阅读障碍干预措施,研究了他们遇到的挑战以及他们如何在课程中利用技术。 It’s a topic that has touched O’Neil personally. O’Neil is dyslexic, her husband is dyslexic, and together they’re raising two dyslexic children. 然而,在南德克萨斯州,有执照的阅读障碍专家很少。 在Coastal Bend,只有两家酒店可供选择,而且都排满了候补名单。

“I asked myself, ‘Why aren’t we exploring virtual reality more intentionally?’” O’Neil said. “As educators, we’re aware that multisensory instruction supports students with dyslexia. Virtual reality is the only technology that truly engages our senses and allows us to manipulate them.”

O’Neil’s interest in virtual reality as a learning tool deepened after she came across a language learning prototype on LinkedIn. The application displayed three floating letters — C-A-T — that each played their phoneme sounds.

“When the user placed the bubble letters together, they popped, and a cat appeared,” O’Neil said. “I considered all of the multisensory layers in that learning activity: audio, visual, touch from haptic feedback, and kinesthetic — That’s when I had the epiphany that VR would be worth exploring for students with dyslexia.”

O’Neil asked Dr. Corinne Valadez ’93, ’95, Professor of Education, to serve as her dissertation chair.

“Aurelia said, ‘I have an idea for a study I would love to do with you,’” Valadez said. “She started telling me about this tethered headset. And I said, ‘Oh my God. 我们之前怎么不这么做呢?’”

这款耳机使用了斯洛文尼亚公司Kobi360的开源VR字母识别应用程序。 O’Neil, working with Valadez as well as research and teaching assistant Lawrence Izuagie ’27, piloted a program with three dyslexic students at a local charter school. 在四周的时间里,每个孩子都参加了简短的五分钟虚拟现实课程,每周三次。 During these gamified sessions, they matched 3D floating letters to their corresponding outlines from a bird’s-eye view. 选择一个字母触发触觉振动并播放其音素,通过多感官输入加强学习。 学生们报告说,他们的字母识别能力有所提高,更重要的是,他们对自己更有信心。

“The students wanted to practice more, they wanted the application to give them more of a challenge, and they wanted new high scores,” O’Neil said.

学习后的访谈也观察到学生自我效能感的提高。

Following their pilot study, O’Neil and her research team were curious as to how XR designers could improve their educational applications with students with dyslexia in mind. 这些问题激发了第二项研究,探索全球XR设计师如何为神经发散型学习者开发应用程序。 Their research was invited for inclusion in the 虚拟现实的前沿 journal and is currently under review.

In April, O’Neil’s research team presented their work at MeaningfulXR 2025, a conference hosted by Stanford University and held on the University of California-Davis campus. 该团队从与会者那里得到了令人印象深刻的反馈。

“She’s standing there rubbing shoulders with people from Stanford and Ivy League schools,” Valadez said. “Not just holding her own, but leading.”

Many of the attendees had never heard of TAMU-CC, but by the time the session ended, they knew all about the Island University, and O’Neil is proud to have earned the university some well-deserved attention.

“We’re the only university that’s leading this kind of research in virtual reality,” O’Neil said. “That has caught their interest. Our Island is now on their radar.”

O’Neil’s path now leads to school districts and dyslexia centers across Texas. 她的论文还调查了全国八位有执照的阅读障碍专家,以确定技术整合的障碍和支持需求。

“They are interested,” O’Neil said. “There’s just not much available and not enough professional development.”

To bridge the gap, O’Neil envisions rental networks for headsets in underserved communities, research-driven prototypes co-developed with dyslexia specialists and educational technology companies, and remote-therapy models that harness the multisensory features of virtual reality to students in remote areas.

Ultimately, O’Neil’s aspiration is to develop a comprehensive program that trains teachers for dyslexia-specialist certification, sustains ongoing educational technology research in the field of dyslexia, and designs a comprehensive dyslexia curriculum, using technology supplementation.

“We’re charting untested waters,” O’Neil said. “But if we can further support dyslexia specialists with quality technology applications, then we’re changing the narrative of what instruction can look like in dyslexia interventions.”